The Spring Equinox is the time of balance between light and darkness, heralding the promise of warmer weather and longer days. The daily rhythm of the rising and setting Sun is one that we cannot fail to notice; even in our electrically powered world we are aware that the Sun, Moon and Earth are somehow bound together in orbital cycles that give rise to day and night, the seasons, and the waxing and waning of the full and dark Moon. But these intricate relationships also give rise to some less well understood phenomena, including solar eclipses and lunar standstills, and there is plenty of evidence from Neolithic stone circles that are ancestors knew about them. Therefore, when I heard that a solar eclipse at the Equinox would have 98% coverage on the Isle of Lewis, location of the famous Callanish stone circles, I jumped at the opportunity to find out more.

The main site at Callanish was built between 2900 and 2600 BCE and is centred round a circle of 13 gneiss stones, from which radiate four avenues towards the cardinal points, roughly in the shape of a Celtic cross. Alexander Thom mapped the site in detail and suggested that the southern stone avenue points to where the midsummer full Moon sets behind the Clisham Hills. [1] There are also theories that the large monolith in the centre of the circle lines up with the avenues to create an accurate north-south meridian, or pole, around which the stars appear to revolve. Given its position in the far north and the availability of some of the most beautiful (and ancient) rocks on the planet, the Lewisian gneiss, it is no wonder that this site is one of the foremost in prehistory.

I joined the other throngs of people at the Stones early on the morning of the Equinox and watched with baited breath as the clouds thinned and patches of blue sky became visible. We were in luck! Though thick cloud cover would have prevented us from seeing anything, intermittent clouds could even enhance the effect of the eclipse through the interplay of the light and the shadow.

It was amazing to see one of Nature’s most admired, and feared, phenomena over Callanish. At the Equinox, the light and the shadow provided by the Sun’s orbital journey are in balance and during a solar eclipse a complementary relationship between the Sun and the Moon is at play. Though the Sun is 400 times larger than the Moon, it also happens to be 400 times further away. So, when the Moon’s orbit comes passes in front of the Sun, it has the effect of blocking out the light for a short period of time, it is eclipsed. The coverage here was not quite total, but nevertheless, the light of the Sun was eclipsed for long enough to witness overshadowing and some interesting light effects. I knew that Callanish was used to observe cycles of the Moon, but had it also been used as an eclipse predicter? I wanted to know about the relationship between the Sun and the Moon so I sought out resident Callanish expert and researcher, Margaret Curtis, to find out more.

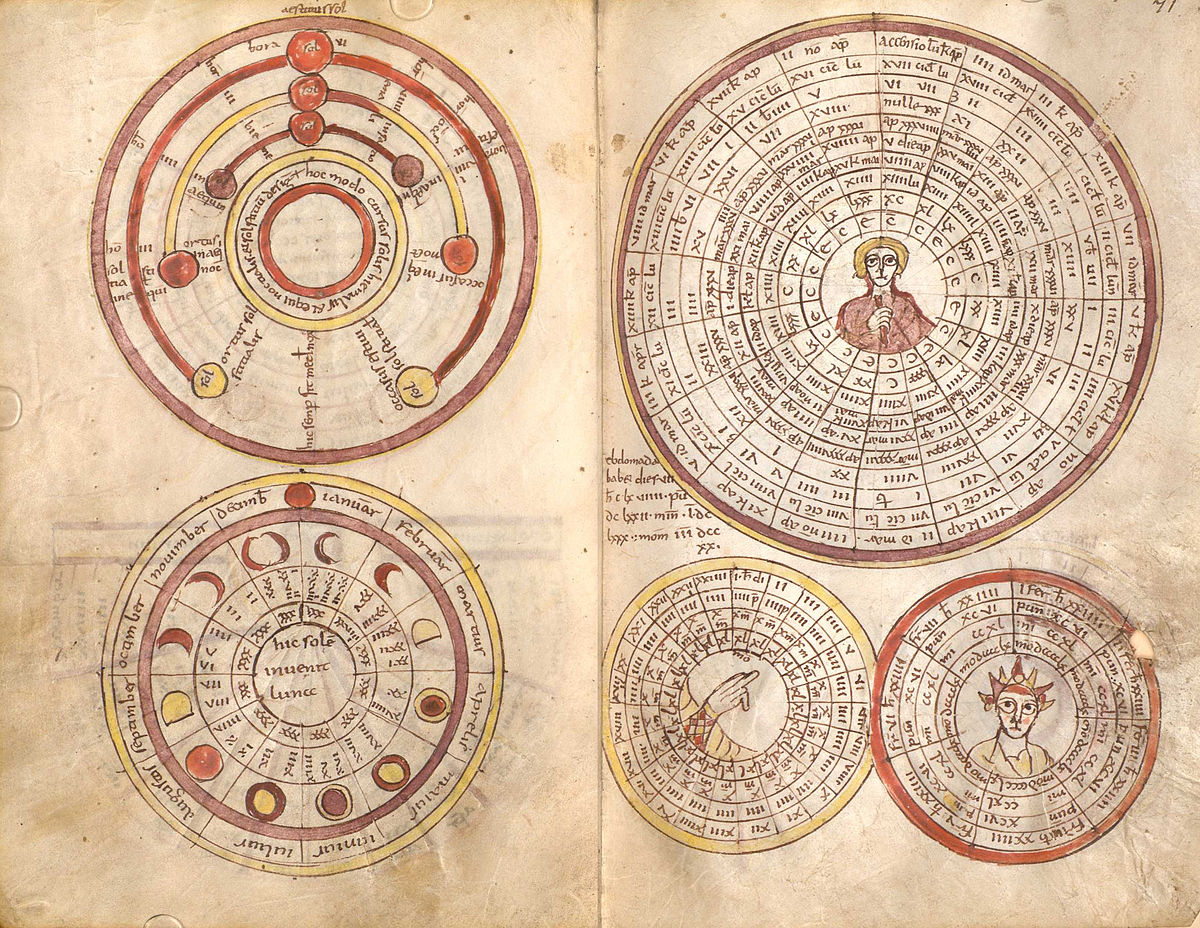

Generally speaking, the cycles of the Moon as viewed from Earth are the opposite to those of the Sun. In the midwinter, when the Sun is at its lowest and weakest, the full Moon is at its highest and brightest. Then at midsummer, with the Sun at its zenith, the Moon is at its weakest. However, over a period of around 19 years, the position of the full Moon around the solstices appears to oscillate and this is due to something called the Moon’s declination. The Moon’s orbit is not in the plane of the Earth’s Equator but inclined to it by approximately 5 degrees. Additionally, as the Earth is inclined at 23.4 degrees to the plane of the Ecliptic (i.e. its tilt angle), this means that the Moon can change altitude in the sky ranging from 28.5 degrees (5.1 + 23.4) and 18.5 degrees (23.4 – 5.1). When at its greatest altitude, the full Moon will rise at its most northerly position in relation to the horizon, appear to hover, then retrace its steps. Two weeks later it will set at its most southerly extreme. Though lunar standstill happen to a degree every lunar cycle, a major lunar standstill (and the opposite, a minor lunar standstill) occcurs only once every 18.6 years, the timespan of the Moon’s precessional orbit.

Alexander Thom first coined the term ‘lunar standstill’ in 1971 after studying the alignments of many Neolithic stone circles in NW Europe, but in particular Callanish. He put forward evidence that Neolithic stone circle builders were not only aware of this phenomenon but used alignments between strategically placed stones and objects on the horizon to map and calculate them. Though his work is widely debated, researchers Ron and Margaret Curtis have continued over many years to investigate the alignments at Callanish.[2] During the most southerly stage of the major lunar standstill, the Moon when seen from the viewpoint of the Stones, rises over a range of hills known as the Old Woman of the Moors (bearing a resemblance to a reclined pregnant woman), skims the horizon and appears to touch the tips of certain stones, before setting, then magically reappearing between strategically placed stones in the central circle. The Moon appears very large and close during this time, and the effect is entirely magical (there are some good videos on U-tube).

Could an understanding of the geodesic relationships between lunar standstills and solstices be used to map and predict lunar and solar eclipses? It could be. In some ways, the standstills are polar opposites to eclipses, but both are linked through the Moon’s nodal cycle. Twice a year, the Moon will cross the Ecliptic, the path taken by the Sun across the sky. When it crosses in front of the Sun, a solar eclipse will happen. During eclipses the Moon is right on the nodes, at standstills, the Moon is at right angles to them.[3] As the builders of Callanish had an understanding of the 18.6 Metonic cycle as referenced in the lunar standstill alignments, could they also have applied this to predict eclipses? This area is certainly worthy of future research.

In March 2014, the Sun and Moon were aligned both to each other, and to the Celestial Equator and the Ecliptic, giving rise to an Equinox solar eclipse. It is fascinating to consider that as the Moon continued on its descending orbital path after this event, it would reach minimum declination over the autumn Equinox (2015), resulting in a minor lunar standstill the following year. Though we can begin to understand these events through science, the full magic of them only comes to life when we experience them. Something our ancestors did over the course of many thousands of years at places like Callanish.

[1] http://www.ancient-wisdom.com

[2] Ron and Margaret Curtis ‘Callanish: Stones, Moon and Sacred Landscape’

[3] ‘The Lunar Standstill Season’ by Jean Elliott at http://www.skyscript.co.uk